Just as I was heading over to Auckland University for my interview with brain scientist Richard Faull, a fellow colleague stopped me at the lift. She told me that she had recently attended a Huntington’s conference where the Professor was a guest speaker - the Huntington’s gene is in her family. This means that there is a 50% possibility of her inheriting the neurodegenerative disorder. But she was hopeful that if anyone could make real progress in the battle against Huntington’s it would be Richard Faull and his team at the Brain Bank.

In 2003 Richard’s research group provided the first evidence that the diseased human brain can repair itself by the generation of new brain cells. As a medical student he was told that was impossible.

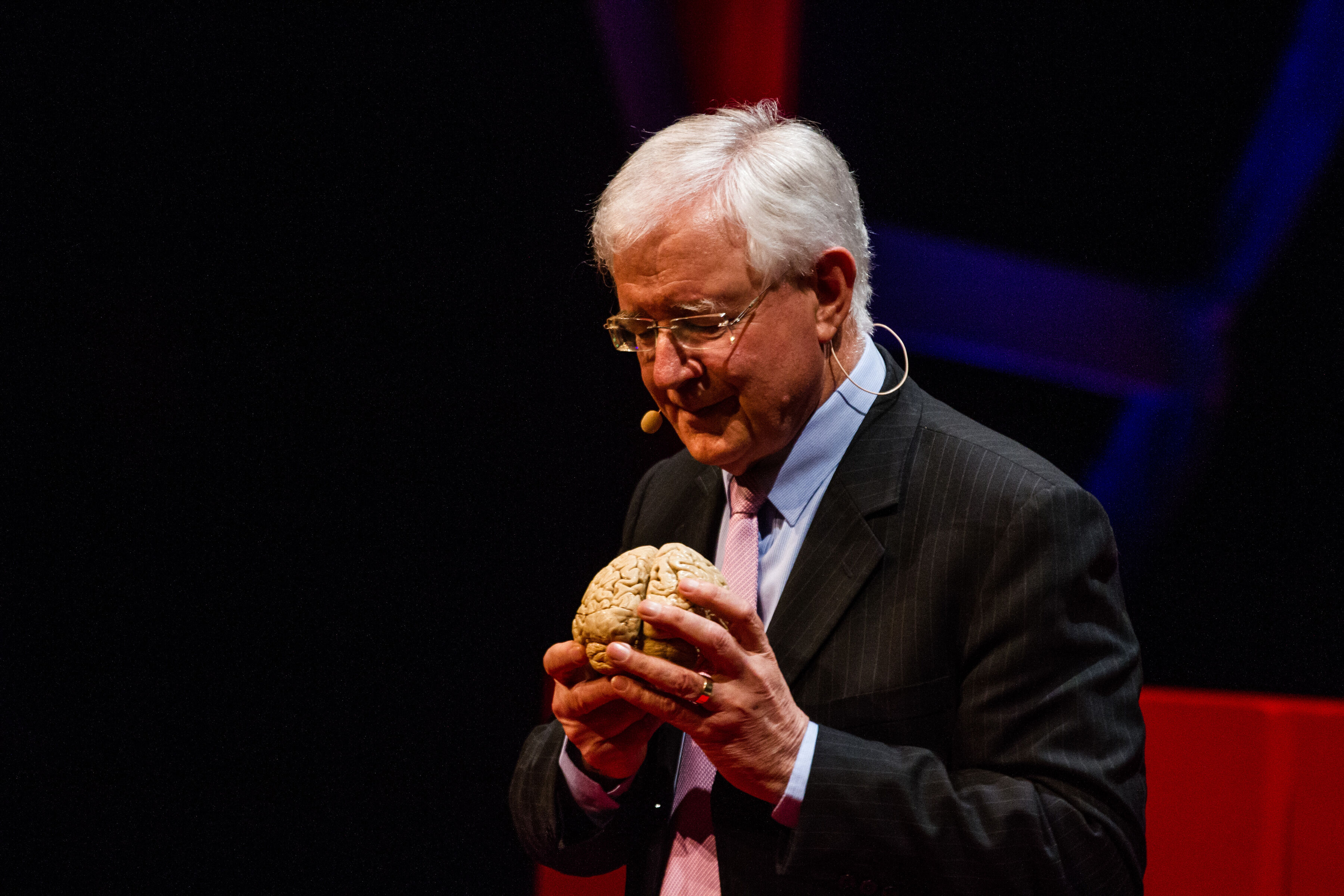

With a research career spanning over 35 years, Professor Richard Faull is recognised internationally as a leading expert on the workings of the human brain and neurodegenerative diseases. This includes Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s. And so I have to admit I was a little nervous about the interview, because I’m not very scientific, but Richard has such a warm and exuberant way about him that within the first five minutes of our meeting I was goggle-eyed enthralled in a lesson of brain science 101.

“New Zealand is an ideal place to study Huntington’s,” he tells me. “Because of our small population it’s a lot easier to trace the family history and communicate with the families.”

Many years ago family members affected by the disease began to bequeath their brains after death so that they could help to determine if their families were affected by this very tragic inherited brain disease, and therefore whether their children were at risk of inheriting the Huntington’s gene.

“I didn’t know I was building a brain bank,” Richard adds. “It grew over 15 years and we found all different things going on in the brain that were not in the text books. We unconsciously set up a programme of brain donation. The only way we knew how to do this was to keep communicating with the families.”

Richard grew up in Tikorangi, a small community in Taranaki, and he says this is where he developed the skills that would play such an important catalyst in his research.

“My mum and dad owned the General store and my brothers and I would help run it. Growing up, learning to talk to people was actually very important,” he tells me. “Now with the Brain Bank we spend a lot of time talking to the families. For us to really understand a person’s brain we had to know the life history of that person. The families are the real heroes.”

During his research, which never really ends, he describes lots of gradual “eureka moments” and unexpected findings. They learned that the brain cells die in different patterns. And so in some brains they saw spotty patterns of degeneration, and in other brains there was a more diffused area with spotty areas more intact. The spotty area was for people with mood problems. And a diffused background was related to movement problems.

“If you had asked me as a young medical student, what’s your blue sky dream? I never thought we would get this far,” says Richard, beaming.

So what next?

“The brain is dynamic in that we are making new brain cells, not just new individual cells, but even the cells that are functioning are changing with every input. The dream is to replace the diseased cells.”

A world class New Zealander, fortunately for us Richard Faull shows no interest in retiring any time soon.

By Jamie Joseph